History of Cape Ann

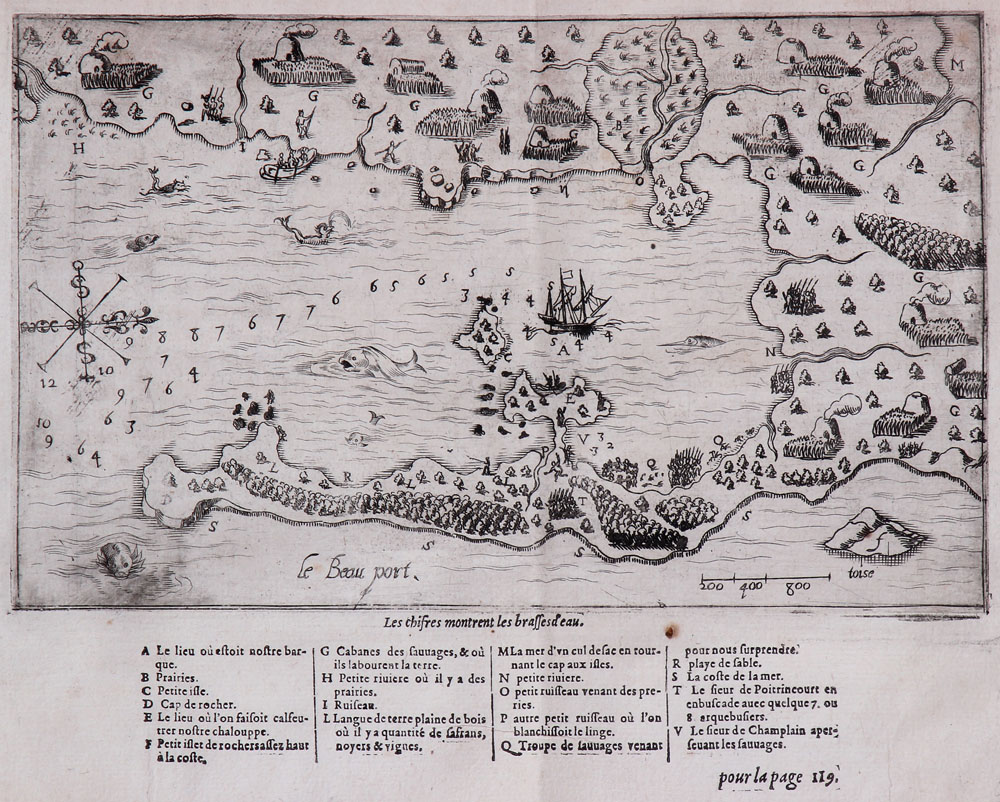

Samuel de Champlain (ca. 1567–1635), le Beau port, map drawn for Les Voyages. Originally printed in Paris, 1613. Cape Ann Museum. Gift of Tamara Greeman, 2011 [acc. #2011.34].

17th Century

When the French explorer Samuel de Champlain made his second trip to Cape Ann in 1606, he came ashore in Gloucester for a peaceful encounter with some of the 200 Indigenous people who were in the area during the summer months. Before he left, he drew a map of Gloucester harbor which he called le Beau port. Eight years later, the English Captain John Smith named the area around Gloucester Cape Tragabigzanda after a woman he met while interned in Turkey as a prisoner of war. Later, England's King Charles I renamed it Cape Ann in honor of his mother Queen Anne.

The Pawtucket people living on the land soon became targets of the settlers. By 1617, the colonists had infested and killed three-quarters of the Indigenous population in Massachusetts by diseases brought from Europe.

By 1623, the English knew there was an abundance of codfish in the waters off Gloucester. The Dorchester Company sent out three ships from England and started a settlement along the coast. A group of colonists from the Plymouth Colony also sailed to Gloucester and built the first racks for drying fish. In the years that followed, both groups experienced difficulty in establishing a profitable operation.

After fits and starts, the settlement of Gloucester continued, and farming became the livelihood of many residents. The General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony incorporated the Town of Gloucester in 1642, and the Governor of Salem began distributing land titles. The Reverend Richard Blynman was the town's first clergyman.

The Town Green, established where Grant Circle is today, was the site of the first meeting house and a number of residences. One of these homes, the White-Ellery House (1710), now owned by the Museum, has survived and is located on Washington Street, not far from where it originally stood.

Documenting African-American History — Little record remains of the lives and experiences of African Americans on Cape Ann in its early years, though ample evidence exists that enslaved and freed African Americans lived here from at least the eighteenth century onward. See some of this evidence and learn more at Unfolding Histories: Cape Ann before 1900 and at the Cape Ann Slavery & Abolition Trust website.

18th Century

The abundance of forests on Cape Ann played a major role in Gloucester's emergence, along with the neighboring town of Essex, as two of the ship building capitals of New England. Early in the century, a new type of vessel was introduced which allowed crews to get out to the fishing grounds faster and make a quick return to sell their catch. For reasons not entirely clear, they were called schooners, and they would dominate Gloucester harbor into the early years of the 20th century.

The vessels made on Cape Ann were used for commercial fishing and foreign trade, and a wide range of supporting businesses were established to maintain the fleet -- sail makers, chandleries, rope walks, marine railways to name just a few. Salted fish was Gloucester's principal export. The goods brought back included wine, fruit, salt, molasses, rum and sugar.

The hardships of the American Revolution devastated Gloucester. Some schooners were commissioned as privateers. They took prisoners of war and claimed enemy supplies at sea. In the end, nearly 400 residents died in battles, shipwrecks and as prisoners of war. British warships all but destroyed Gloucester's fishing fleet and interrupted the profitable trading established in previous years.

By the end of the century, however, recovery was well under way. With the growing focus on maritime activities, the town center moved to the harbor, merchants opened their doors to sell a wide variety of goods, and prosperous traders and ship captains built substantial houses near the harbor.

![Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865). Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, 1844. Oil on canvas. Gift of Jane Parker Stacy, 1948. [Acc. #1289a] Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865). Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, 1844. Oil on canvas. Gift of Jane Parker Stacy, 1948. [Acc. #1289a]](/media/uploads/gloucesterrockyneck1844.jpg)

Fitz Henry Lane (1804–1865), Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, 1844. Oil on canvas. Gift of Mrs. Jane Parker Stacy (Mrs. George O. Stacy), 1948 [#1289.1a].

19th Century

Fitz Henry Lane, who would become a maritime luminist artist and one of the country's most important painters, was born in Gloucester in 1804. Itinerant artists came to paint portraits, but the mainstream of Cape Art was soon taken over by seascapes and landscapes. In the middle of the century, the completion of a rail link to Boston made it easier for artists to visit Gloucester, and the town's natural beauty made it a favorite of artists such as Winslow Homer.

The fisheries prospered at mid-century and fortunes were made in trade with the Dutch colony of Surinam. Gloucester businessmen provided low grade salted fish to feed black slaves and brought back molasses which was sold to Boston merchants to be made into rum.

→ Read about Fitz Henry Lane and the Surinam Trade here.

The appearance of the town was radically altered by two fires. In 1830, much of the downtown area burned. Following this fire the historic West End - as the western end of Main Street is known - was rebuilt using granite and brick in place of wood. Then in 1864 a second fire ravaged the city, causing many of the wooden buildings that lined the harbor to be lost.

Gloucester's granite industry began in mid-century, with retired army general Benjamin Butler leading the way. Immigrants from Finland, Sweden and Ireland found work in the quarries, adding variety to the town's existing population of English descendants. New vessels called stone sloops were designed and built to carry granite to ports along the eastern seaboard for use in Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.

During the 1840s, immigrants from Portugal (particularly the Azores) came to work in the fishing industry. They brought new ideas and customs to Gloucester and in time became owners and operators of large vessels. Just before the turn of the century, immigrants from Italy began coming to Gloucester to seek opportunities in the fisheries. They, too, brought a vibrant culture, and they became a dominant force in the fishing industry.

The same railroads which brought an influx of artists to Gloucester also expanded opportunities for land-based trade and opened up the area for tourism, which was destined to emerge as one of the city's major industries.

![Lighter Jonas H. French loading for the Cape Ann Granite Co. at Lane's Cove, c. 1899. Barbara Erkkila Collection. [Acc. #1994.76] Lighter Jonas H. French loading for the Cape Ann Granite Co. at Lane's Cove, c. 1899. Barbara Erkkila Collection. [Acc. #1994.76]](/media/uploads/loading_granite.jpg)

Lighter Jonas H. French loading for the Cape Ann Granite Co. at Lane's Cove, c. 1899. Barbara Erkkila Collection [1994.76].

For further exploration