Gloucester’s Ties to the Surinam Trade as Evidenced in the Work of Fitz Henry Lane

Works of art often provide clues to the culture and events of the time period that they portray. Therefore, scholarship within the field of art history can not only be about understanding the development of art but also about examining the historical context that the art records. As Lane’s career covered the first half of the 19th century and he lived and worked in a thriving seaport, it stands to reason that his subject matter most often focused on the maritime activity around him. Consequently, his paintings offer the opportunity to study that industry as it unfolded in Gloucester during his time.

One of the more common subjects in his marine paintings is his portrayal of ships involved in the Surinam trade. Recent research, the frequency with which Lane incudes these vessels in his scenes of Gloucester harbor, and the many commissions from such ship owners indicates just how important a part of the Gloucester economy that type of trade was during this period. But what exactly did trade with Surinam entail, and what made it such a lucrative and subsequently attractive prospect for ship owners, captains, and investors at this stage of Gloucester’s history?

The English established the first plantation colony in the area known as Surinam on the northeastern coast of South America in 1650, and in 1667, control of the colony passed to the Dutch as part of a trade for New Amsterdam (now New York City). Surinam flourished as a plantation economy that was fueled by the labor of enslaved people imported from West Africa. The most profitable commodity that Surinam produced by far was sugar, while other exports included coffee, cotton, and indigo. Although sugar was economically rewarding, its harvesting and processing were notoriously dangerous, which resulted in a very high death toll among the enslaved laborers. Surinam plantation owners also earned a reputation for exceptionally cruel treatment of the slaves under their jurisdiction. By 1750, there were at least 500 sugar plantations operating in Surinam.

Along with the West Indies, Surinam grew to become a significant marketplace for salt fish because it was a cheap source of food for the substantial number of enslaved captives that worked on the plantations. In 1717, two Gloucester ships are on record as having travelled to the West Indies to trade salt fish for sugar, and Rhode Island merchants monopolized this type of barter with Surinam for much of the 18th century. By 1776, there was enough foreign commerce in Gloucester harbor to require the installation of a customs inspection office there, and from 1790 to 1840, Gloucester vessels in turn emerged as the primary suppliers of salt fish in exchange for sugar with Surinam.

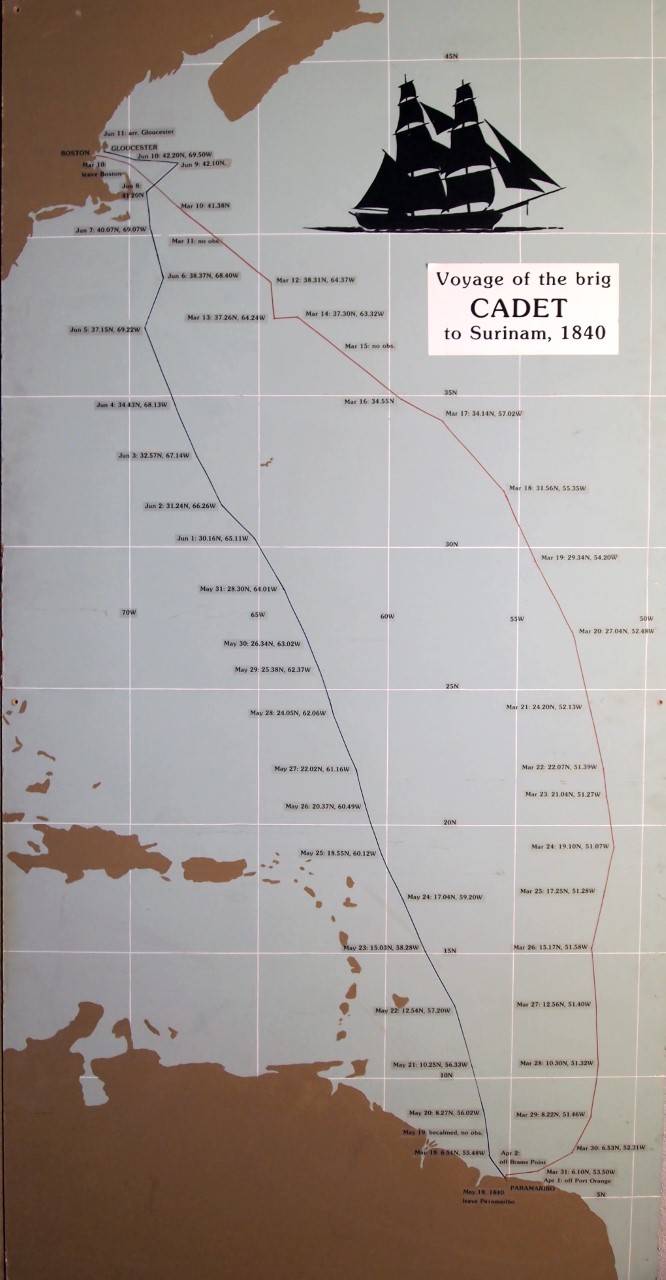

Evidence of Gloucester ships travelling to Surinam during this period can be found in many archival resources. In the Cape Ann Museum’s Archives, the “Ships Log Book Collection” is comprised of 73 ships logs from the period 1751-1935, and they record nine trips to Surinam between 1837 and 1863, including one by the “Cadet” in 1837-41 under the command of Captain Edward Babson. Six of these nine trips track voyages that were undertaken by Captain Nehemiah Cunningham, who purchased a wharf at Fort Point from George H. Rogers in the late 1860s and turned primarily to fishing later in his maritime career. Another reference, this one published in 1882 and known as The Fishermen’s Own Book, reports 93 trips to Surinam by Captain William Tucker, a resident of Gloucester, between 1843 and 1881.

(left) Chart showing the voyage of the brig Cadet to Surinam and return, March 10–June 11, 1840, c.1980. Painting on board. Collection of Erik Ronnberg; (right) Captain Nehemiah Cunningham, Captain of the Brig Cadet. Photography by W.A. Elwell. Collection of the Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA.

After unloading their cargo holds of salt fish in Surinam, ships returned to Gloucester laden with molasses for processing rum as well as coffee and European goods such as silver and delft china. During the 1850s at the height of the Surinam trade, ship owners and investors could realize a 5 to 10-fold profit over their original outlay, and the degree to which money from this type of commerce flowed into the town of Gloucester fueled an economic boom that in time financed a substantial part of the area’s future growth in commercial fishing.

By 1860, the Surinam trade in Gloucester was beginning to wane due to a series of events. For example, some of the larger commercial shipping firms had relocated to Boston because of modifications in trade regulations and the need for more robust facilities and a deeper harbor. In 1863, the Netherlands abolished slavery in Surinam, although most of the enslaved were not fully released until 1873. During this same period, developments in fishing techniques that allowed fishermen to bring in greater quantities of cod, mackerel, and halibut, improved refrigeration capabilities, and the completion of the railroad from Boston enhanced Gloucester’s ability to more readily compete in the fishing industry.

(left) Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865), Brig “Cadet” in Gloucester Harbor, late 1840s. Oil on canvas. Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Gift of Isabel Babson Lane, 1846 [#1147a]; (right) Unknown, Portrait of Captain Edward Babson, late 1840s. Oil on canvas. Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA.

Many of Lane’s clients were Gloucester residents involved in trade with Surinam who took great pride in their vessels and commissioned him to paint them. Brig “Cadet” in Gloucester Harbor from the late 1840s shows a ship owned by Captain Edward Babson, one of the most prosperous Surinam merchants of the period, gloriously portrayed with sails stretched full and her pennants flying. The “Cadet” was a type of brig with a wide hull, and the extra cargo capacity made it the primary vessel of choice for traveling to Surinam, so much so that at times the style was referred to as a “Surinam brig.”

Vessels such as these can also be seen in many of Lane’s paintings of Gloucester harbor, including The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1847, and Gloucester Harbor, c. 1852, as well as his 1846 lithograph View of Gloucester from Rocky Neck. Lane’s painting A Rough Sea, 1854, is another work with this type of ship as its focus and was commissioned by Obadiah Woodbury, a Gloucester Surinam trader in partnership with George H. Rogers. Lane’s 1857 work, Three Master on the Gloucester Railways, shows Rogers’ brig “California” under repair, a vessel that had made at least one trip to Surinam under Rogers’ tenure before its destruction in a storm in 1857.

Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865), A Rough Sea, 1854. Oil on canvas. Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Gift of Prof. and Mrs. Alfred Mansfield Brooks, 1938 [#807].

Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865), Three Master on the Gloucester Railways, 1857. Oil on canvas. Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA. Deposited by the City of Gloucester, 1952 [#DEP.202].

Lane passed away in 1865, and as such, his artistic career almost perfectly mirrors the period of time during which trade with Surinam was the port of Gloucester’s most profitable area of foreign commerce. With their focus on marine painting, his works now give us valuable historical insight into the impact of that trade on the town of Gloucester in terms of the quantity of ships engaged in the practice and the number of individuals whose fortunes grew from it. In its quest to thrive as circumstances changed, Gloucester rebounded from the decline in trade with Surinam through diversification and ultimately flourished with the fishing industry. But there is little doubt that the tremendous economic gains realized during the peak of the Surinam trade helped to lay the foundation for the town’s future success.

→ Read about a Museum volunteer effort that has transcribed a set of ships logs from 1781-1807. These records detail 57 voyages of Captain Elias Davis, whose trade in salt fish to feed the enslaved populations in the Caribbean predated Lane’s artistic career here.

→ Learn more about Cape Ann’s connections to slavery throughout history at capeannslavery.org.

→ Learn more about the history of African Americans on Cape Ann in this online exhibition.