Cape Ann Beacon: How a statue of Masconomo made it to Manchester

November 25, 2020

The Cape Ann Museum celebrates Cape Ann as a place, and an important part of its legacy is our area’s Native American history. In this multi-part series of articles, the Cape Ann Museum provides a preliminary insight into Indigenous peoples of Cape Ann as part of the Museum’s desire to strengthen an understanding of this story. Moving ahead, CAM looks forward to partnering with organizations, scholars and descendants of the Cape Ann Native American population to ensure that this significant narrative is appropriately documented and shared broadly within the Cape Ann community and beyond.

The word “Masconomo” is familiar to many on Cape Ann as the name of a waterfront park and tree-shaded street in Manchester-by-the-Sea and has been referenced as the name of the first Native American to greet the Arabella when it arrived offshore south of present-day Manchester Harbor in 1630.

However, hidden in plain sight in the foyer of Manchester Town Hall sits one of the more fitting tributes to this important figure from the town’s past, a bronze sculpture of Masconomo by 20th century artist George Aarons.

George Aarons (1896-1980) was born in Lithuania and immigrated to the United States with his family when he was young. He attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and regularly visited Cape Ann in the 1940s, finally moving here year-round in the 1950s.

During the 1930s, he began working under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) creating sculpture for public installations. In 1938, the WPA proposal from the town of Manchester-by-the-Sea called for the creation of a life-size statue to commemorate “Chief Masconomo” that would be placed in Masconomo Park.

Throughout Aarons’ career, his style would evolve from realistic to an increasingly abstract approach. Many of his works focused on the human form, and he maintained an interest throughout his life in conceptualizing the universality and humanity of struggling to thrive with dignity in a world that could often be cruel.

Maybe it is no surprise then that when Aarons was awarded the commission for a sculpture to commemorate Masconomo, he created an image about as far from the then-popular trend of depicting Native Americans as grinning figures in feather headdresses and fringed leather garb as could possibly be imagined.

When he submitted his prototype for approval in 1938, Manchester town officials rejected his sculpture because it lacked just those characteristics that today we know are a false representation of Native American appearance in the 1600s.

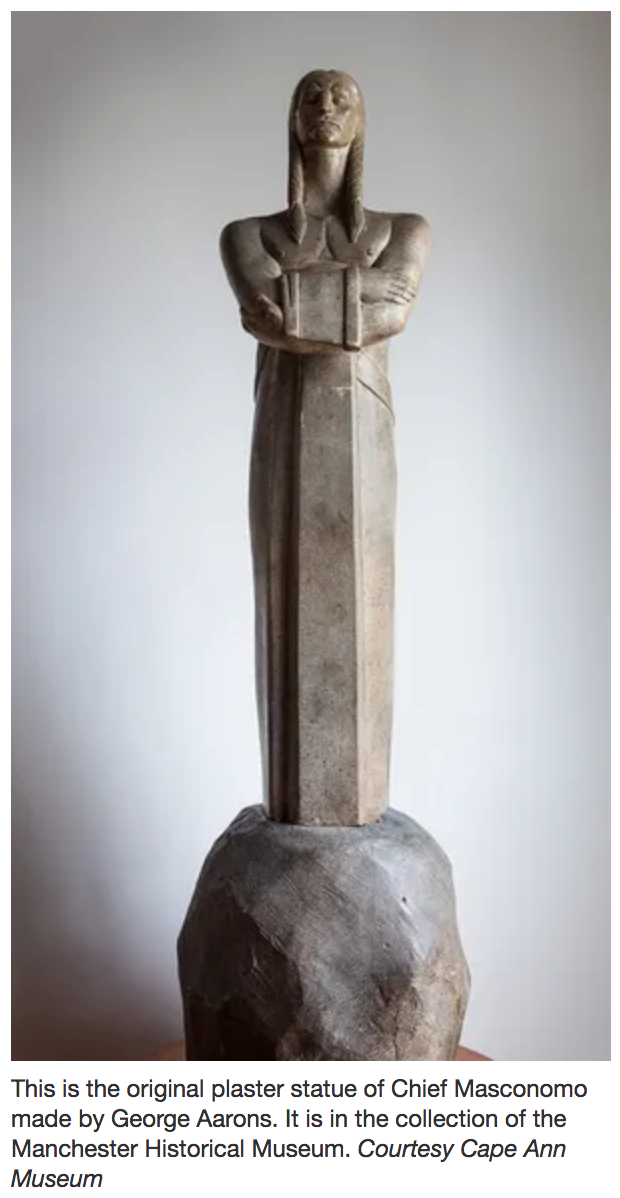

In the early 1980s, a group of Manchester townspeople learned about the errant project and purchased the plaster model from Aarons’ widow. Unable to afford the cost of casting a life-sized bronze, the group succeeded in having a statue the same size as the model cast and installed on the first floor of their Town Hall, while the original plaster model is currently on display at the Manchester Historical Museum.

So, the next time you are in town hall paying your taxes or a parking ticket, take a moment and pause at the unassuming bronze sculpture that stands just to the left of the treasurer’s window. Notice the simple dignity of the squared shoulders and lifted chin, the quiet wisdom of the folded arms and closed eyes, the strength and vulnerability of the bare upper body and the solidity of the columnar form anchored to the earth.

Today, no one knows for certain what Masconomo looked like. What he thought about the folks that arrived in the Arabella and the events that transpired over the ensuing years as the land he had relied upon for sustenance was gradually bargained away from him until he died in poverty in 1658 is an ongoing investigation.

But there is a chance that the artistic vision of George Aarons has captured the collective courage that would be required to face a future that would prove to be increasingly uncertain and uncontrollable.