Cape Ann Museum show looks at painters' love affair with Gloucester

August 3, 2017

By Cate McQuaid - Globe Correspondent

August 03, 2017

GLOUCESTER — The great painter Stuart Davis, before he shook loose from realism into flattened, abstracted cityscapes and still lifes, was drawn to Gloucester because, he wrote, “it had the brilliant light of Provincetown, but with the important addition of topographical severity.”

That severity — granite quarries, waves exploding on rocks, knotty ropes and docks — makes “Rock Bound: Painting the American Scene on Cape Ann and Along the Shore,” at the Cape Ann Museum, a bracing, wind-stung exhibition, sometimes warmed by the summer sun.

Childe Hassam, Marsden Hartley, and Milton Avery all painted in Gloucester, filtering its seascapes and street scenes through American Impressionist and realist lenses. The two Davis paintings here are from the 1910s, before he shook loose from realism into jazzy abstraction, but “The Importance of Place: The Sketchbooks of Stuart Davis,” in a neighboring gallery, presents wily drawings that perch at abstraction’s edge.

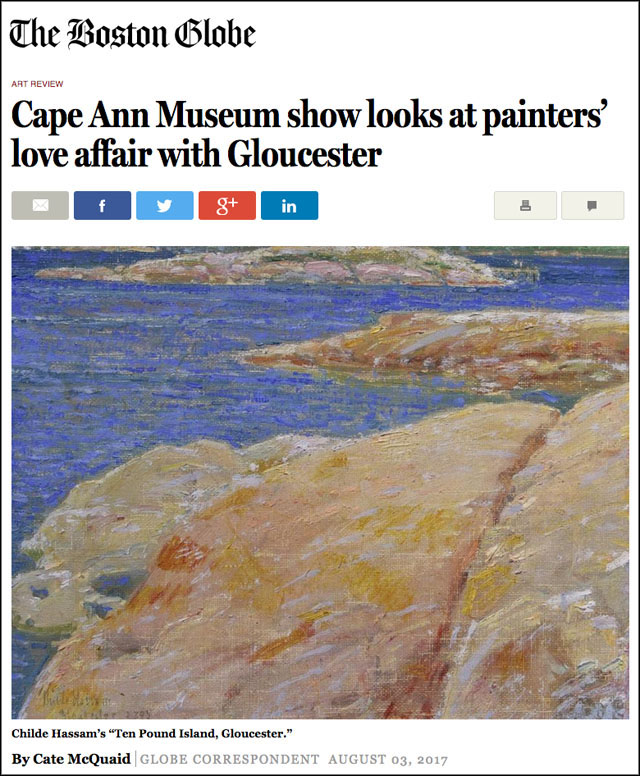

The earliest work in “Rock Bound” is Hassam’s 1895 painting “Ten Pound Island, Gloucester,” depicting reddish land against a periwinkle sea. Just a play of land and water, it’s not his most sophisticated piece. Still, it gleams. Here, form is merely the flint upon which to ignite light’s energy.

By the time Hassam arrived, Gloucester had for decades been developing a sideline in tourism. The railroad came in 1847, and with it the leisure class and artists, who set up shop in fishing shacks along Rocky Neck, one of America’s first artists’ colonies.

A bit of touristy kitsch, a mirror made around 1920, hangs in the middle of the exhibition, with “Gloucester” written along the frame’s bottom. Panels on either side feature able paintings of Good Harbor Beach. One portrays a pair of women in long dresses ascending a steep little footbridge over a channel. It kicks off a lovely sequence of later works in the show, from the 1930s and 1940s.

Avery’s “Bridge to the Sea” must depict the same bridge, quickly curling into the distance. Again, two figures, here wavering like mirages, cross away from us. Avery’s colors, sweet and piquant pinks and oranges, with green making a minor key, glow with the melancholy of late summer sunshine. The whole thing seems a dream, or a potent memory so inflected with feeling that it only tenuously connects to reality.

Beside it hangs Sally Michel’s watercolor “Watching From the Shore.” Michel was Avery’s wife — they met in Gloucester and spent several summers here. In some ways she took after him. But this painting tells a story, and Avery favored form and color over narrative. A woman and a girl on a cliff watch a ship capsize just offshore. The year before, the Gen. MacArthur, a fishing boat filled with mackerel, had run aground at Eastern Point.

The works by Avery and Michel are eloquently spare. Most of the paintings in “Rock Bound” are weightier, close-packed with gesture and form. One of Hartley’s exquisite Dogtown paintings, “Rock Doxology Dogtown,” makes the perfect pivot from realism to the leaner work of Avery and Michel: plangent and gravid with boulders but still pared to a simple rhythm of shapes and curves.

Compare that to Frederick J. Mulhaupt’s more densely orchestrated “Winter Harbor,” painted in 1920. The key tone in Mulhaupt’s scene, as in Avery’s, is pink. Moored boats stand idle amid patches of pink ice. The warm hue softens the grit and bite of winter along the water, a desolate scene of slack sails and barren branches.

William Glackens’s “Beach at Yellow Island,” meanwhile, has all the heat of a fever dream, shimmering with impressionistic brushwork. The Ashcan School artist displays a Fauvist streak here, conjuring up a rose gold island in a sea of dappled blue. Four women stand in black swimsuits in the foreground, a dark counterweight to the dazzle in front of them. They seduce in line, not color, with brush strokes caressing their long locks and knee-length frocks like ribbons.

Davis studied with Ashcan School leader Robert Henri, and the stalwart realism of that aesthetic prevails in his “Rock Bound” paintings. Still, you can sense the sheer motion and zigzag to come in “Gloucester.” A generous landscape ripples around two small, separate figures: ocher trees, burgundy hill, swaths of green and gray. The distant water looks buttery under a gray sky.

Davis’s sketchbooks make quite the chaser, gin to “Rock Bound”’s stout. In a 1916 sketch, “Gloucester Terraces,” two figures in black anchor a foreshortened street scene that shoots up like a roller coaster. A towering turret dominates the background; greyhounds leapfrog over tiers of land. The exaggerated steepness threatens to yank the rug out and fling the scene into disorder.

Many of these sketches became material for paintings Davis made in the 1930s. One sheet has crisp port drawings, busy with pylons, nets, and masts, which led to two works, “Dock, Still Life” and “Black Roofs.”

Their jaunty jumble, all shapes, lines, and intersections, capture what the eye sees just before it makes meaning. In the finished works, color would orient the viewer. Here, though, there’s a frisson in knowing where we are, but not being able to immediately place ourselves. And with that, realism’s rocky severity celebrated in “Rock Bound” gives way to the fracas of Cubism.