The Life Line—Looking Beyond the Margins

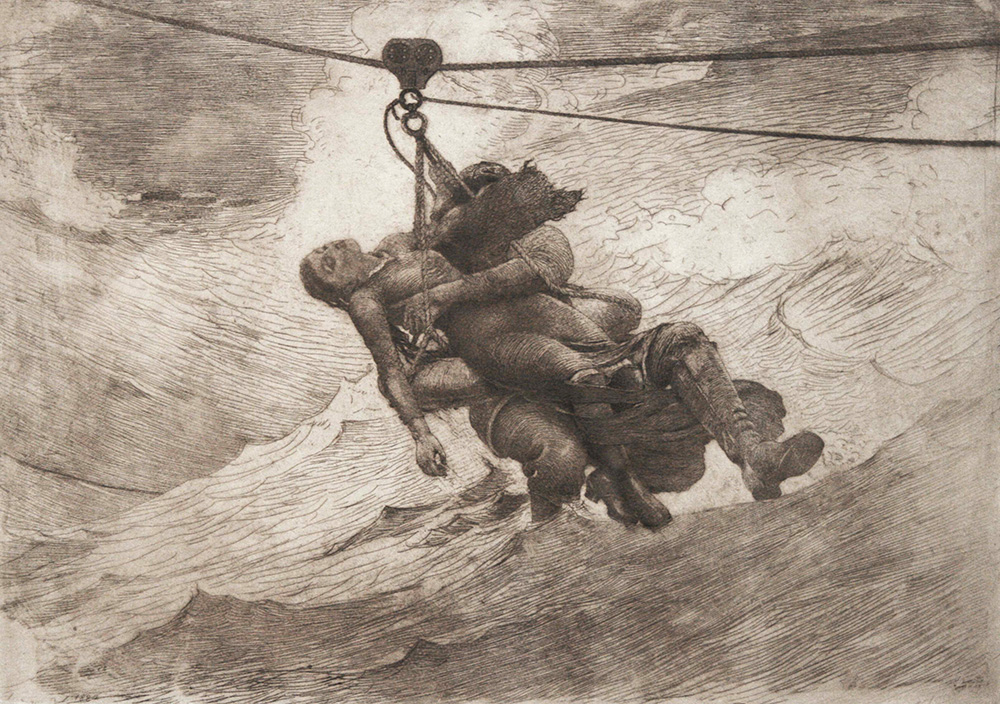

Winslow Homer’s oil painting The Life Line, completed in 1884, was to become one of his best-known works—and it remains so to this day. While the storm-driven water and sky provide the drama, the title and its subjects provide the element of suspense (and suspension) made possible by an improved technology for transporting people from a wrecked ship to the shore. This was achieved by means of a life line fitted with a traveling conveyor for the survivors called a "breeches buoy." In focusing on the buoy and its occupants however, Homer (justifiably) omitted the rest of the life line and the equipment needed to move buoy and passengers to safety.

Getting a rescue line from shore to ship was the first of many problems addressed in the early 19th century by English lifesaving stations, followed closely by the French. Mortars with projectiles attached to a line, and rockets with lines in tow, were tried with mixed results. It was not until 1876 that the U.S. Life Saving Service was established and a serious effort was made to improve the technology. In 1877, U.S. Army Lieutenant David A. Lyle was appointed to address the problems, starting with the guns used to send a messenger line from shore to a vessel in distress.

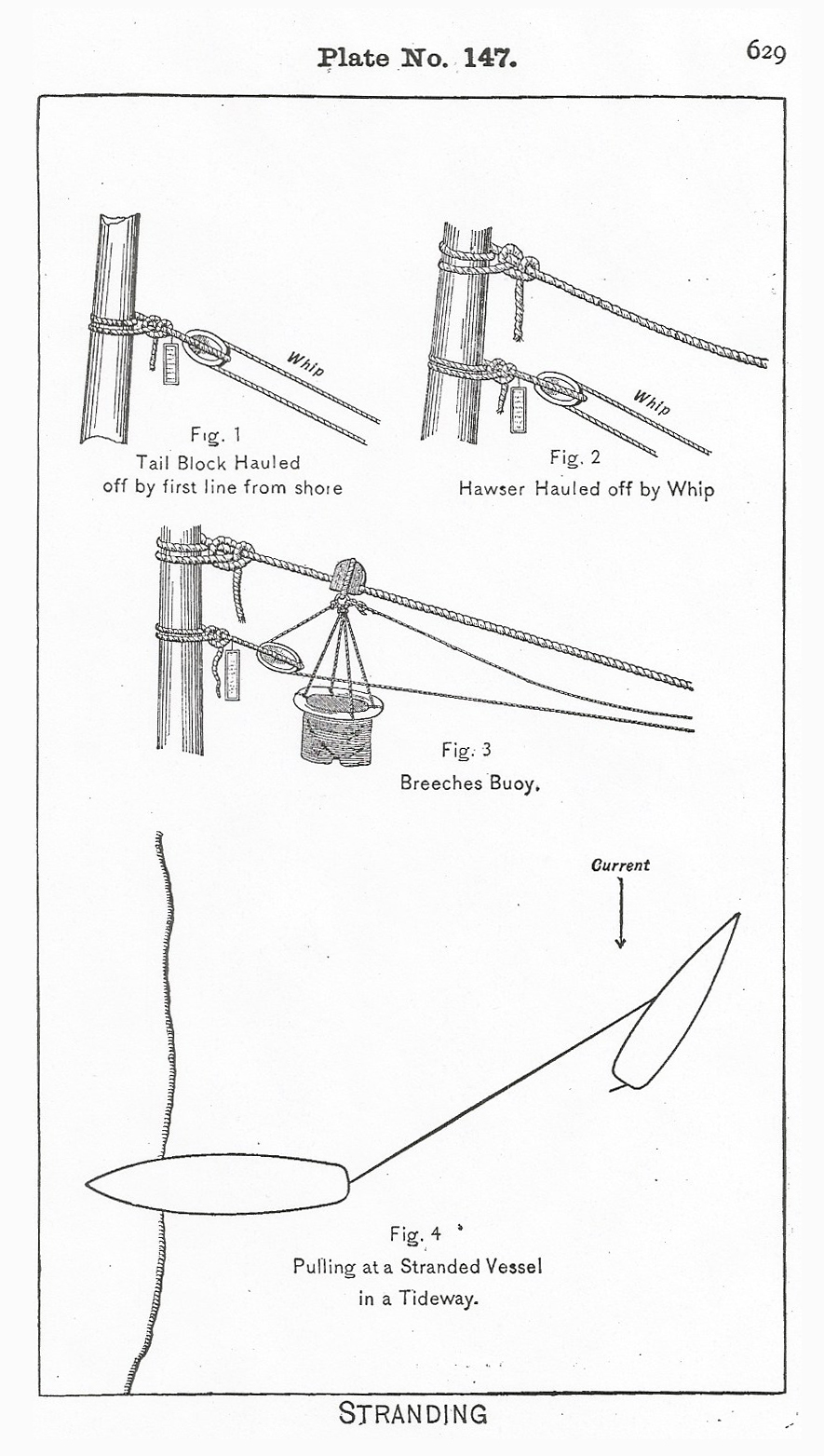

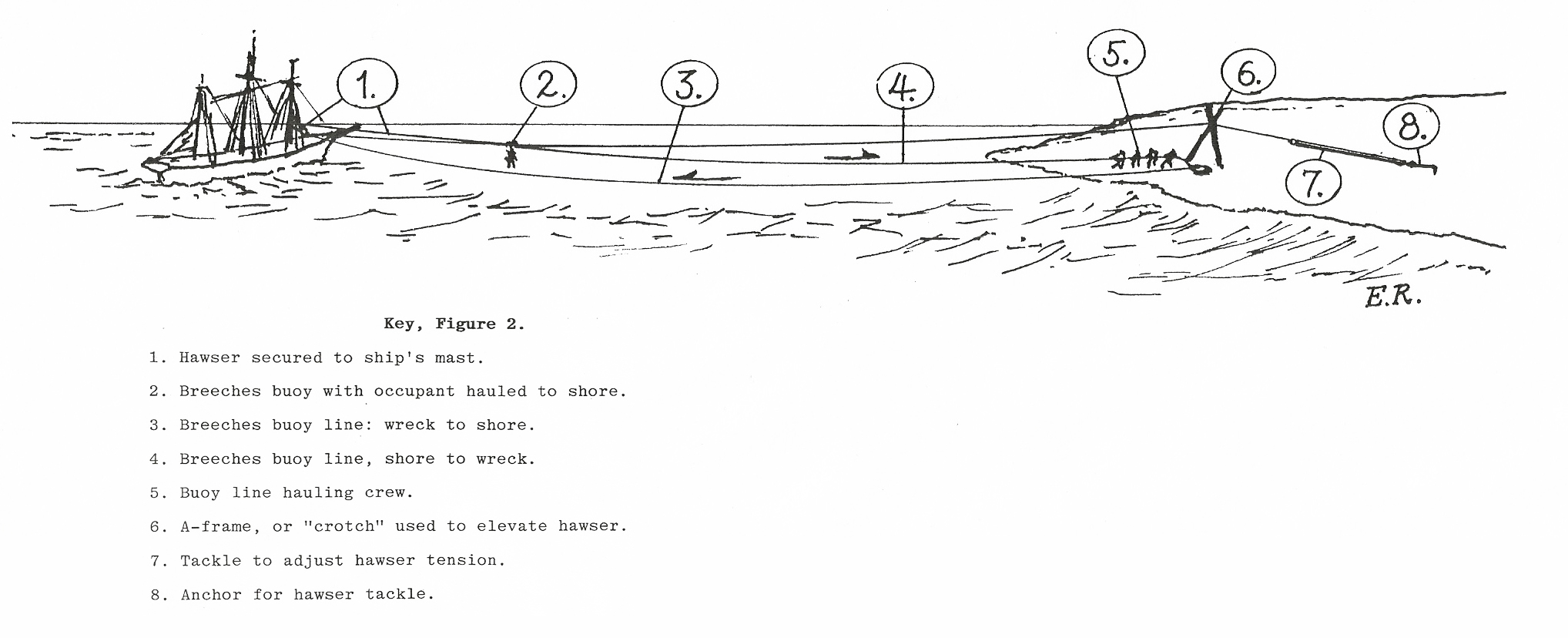

His solution was a light-weight mortar that fired a projectile with a messenger line attached. When the line reached the ship, it was hauled on board. Attached to the line was a “tail block,” with a line rove through the block called a “whip” (see Figure 1). The whip was the line by which the breeches buoy was hauled out to the vessel and then back to shore with a rescued crew member and/or passenger. Before that process could begin though, a third, much heavier line called a “hawser” was hauled via the whip to the wreck and tied to the ship’s mast just above the whip’s block. It was the hawser that bore the weight of the breeches buoy and its occupants en route to shore. The hawser was held taut at the land-end by a tackle anchored in the soil well back from the shore. It was also elevated at the shore by a wooden A-frame (called a “crotch”) to keep the buoy and its occupant out of the surf (Figure 2).

The greatest problem in making this system work smoothly was the mortar that shot the messenger line to the wrecked ship. Lieutenant Lyle developed a very light mortar which fired a carefully machined projectile with an iron shank connected to the messenger line. To reduce shock, which could break the messenger line, a “mild” gun powder was used, which also reduced recoil. The range of this combination was over one-fifth of a mile, with aiming accuracy of fifty feet or less to either side of the point of aim at the ship in distress.

Despite competing technologies, Lyle’s mortar and gear remained in use with only minor improvements until the mid-2oth century, when it was finally superseded by rockets. This was a remarkable achievement for a technology used for seventy years with few changes, while maritime technology around it evolved profoundly. Even after 1952, when production of the Lyle guns ceased, their use abroad continued for many more years.

→ Read more about "Rescue by Breeches Buoy" here

References

P. Barnett, “The Lifesaving Guns of David Lyle,” Nautical Research Journal, Vol. 19, No. 1, Spring, 1972, pp. 21–26.

Austin M. Knight, Modern Seamanship, 7th ed. New York: D. Van Nostrand Co., 1977, pp. 629, 633–636, plate 147.

Raymond J. Lamont (Ed.), Gloucester: America’s Oldest Seaport. Gloucester, MA: Pediment Publishing, 2015, pp. 100–101. (Photo in Cape Ann Museum Collection, image no. 16506).

Images of America series. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

Paul St. Germain, Lighthouses and Lifesaving Stations on Cape Ann (2003), p. 25.

Carolyn and Jim Thompson, Cape Ann in Stereo Views (2000), p. 92.